As part of my OU Art History studies I took part in an inconclusive and ultimately unresolved debate, from my point of view, about exactly what is public art.

The debate was instigated by an article in the Guardian in which Anthony Gormley castigated most public art as ‘crap’ , according to the article, his view was supported by others in art world:

Reluctantly, I have to agree with them as I believe public art has to be not just physically open and accessible to all who funded it but also, the work must have meaning to and inspire the community, which financed its execution and finally great public works become local, national & ultimately international icons for their communities, here I have in mind America's Mount Rushmore or Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer or Copenhagen’s The Little Mermaid.

Sadly many modern public works are the opposite – meaningless and depressing – ignored, forgotten and past over, left to decay.

However following my time at the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow I have now found a public work of which ticks all the boxes.

The traffic coned equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington by the Italian artist Carlo Marochetti erected in 1844 on a 10ft plinth outside Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) is for me is a real piece of truly public art as it’s very open, it’s very accessible, it means a lot to the locals. Attracting 10,000 signatures to a petition , with another 45,000 people showing support on Facebook when the council considered making it impossible to place a cone on the statute, plans it eventually had to drop in the face of such public pressure. It's been inspirational and has become an even much more loved icon for the city after winning the battle with the council.

Appropriation Art

GOMA's conned Wellington is a classic example of intervention or appropriation art - the intentional borrowing, copying, and alteration of preexisting images and objects - but most importantly there is no plagiarism, no copyright theft, no litigation, no cynicism, no bullying and no deceit along with the down right lying found in many other examples of contemporary appropriation art.

GOMA’s coned Wellington is an honest appropriation.

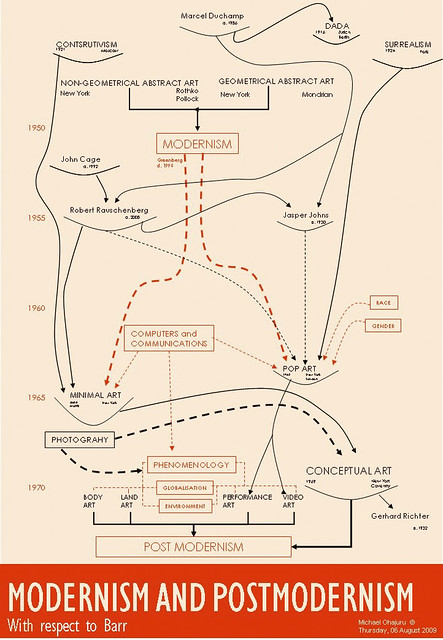

The modern practice of appropriation can perhaps be dated back to Duchamp and his ‘assisted readymades’ (a title this blog appropriated) where, for example he appropriated The Mona Lisa to create ‘his’ LCHQQ.

While Banksey has turned approbation into a key part of his oeuvre as seen in how he intervenes in a Rembrandt self portrait or how Michelanglo’s David is appropriated into a suicide bomber or Monet’s Lily Garden into a polluted lake.

Both Duchamp or Banksey took the work of old deceased masters sadly, other artists choose to appropriate the work of living artists, passing it off as their own original work with no reference to the source – often ending in court where the matter is most times resolved in favour of the artist who has appropriated the work who claims ‘fair use’.

Richard Prince appropriated Patrick Cariou's Yes Rasta series of photographs to create his Canal Zone series of images, selling tens of millions of dollars with no permission from or reference to Cariou's work. An approbation that went to court and sadly Prince was deemed to have made 'fair use' of Cariou's work.

|

| Left Cariou Right Prince |

|

| Left Lang Right Morris |

However there is something else going on with GOMA’s coned Wellington as it also represents the wit, the humour and tolerance of the people of Glasgow. The Glaswegian response to the Wellington approbation was very different to the response to the Banksy like approbation of Churchill's statue in London's Parliament Square, which was rooted in the anger and violence of anti-capitalist May Day riots.

Iconic Public Art

The people of Glasgow have not only created a legally appropriated work of art but a great iconic work of public art which, appropriately took centre stage as one of the icons of not just the City but of Scotland, at the opening ceremony of the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow this summer.

-3_new-2.jpg)